Notes and Spoiler Alerts

This piece will contain spoilers for SuperGiant Games’ other titles, including Bastion (2011), Transistor (2014), and Pyre (2017). If you’ve never played those titles, I really recommend you do!

It will not go into over-arching plot spoilers for Hades, but if you’re looking to go into the game completely fresh, I recommend you skip this piece for now.

This article has a number of animations, webMs and videos! Feel free to click on them to have them play. They should default to whatever format is playable on your browser.

This article was written with the support of my lovely patrons on Patreon.

I’ve been a fan of SuperGiant Games from the first time I played Bastion, released in 2011. Their games have a very focused and unique way of telling stories through narration, and their gameplay tends to be quite similar, as well: top-down, isometric combat that seeks to mix in your reflexes with knowledge of their systems.

Their latest game, Hades, has gotten a lot of positive press from being a great example of how Early Access is supposed to work. The game has blossomed with content through its journey, and has reached 1.0 in a state that’s impressive.

I’ve resisted playing the game for a bit, mostly because of the nature of its roguelike system. You’re meant to play it, and play a lot of it to get everything it has to offer; when I’m looking at my backlog now, I’m more concerned about getting through single-serving titles (play once, and then finish), rather than sitting down for an extended stay at the buffet.

But, somehow, it pulled me in. Twenty-something runs later, I felt the need to write something about it; while I’m not done with the game by any means, I feel like I “get it” enough to be able to talk about how it pulls from SuperGiant’s previous games, successes, and failures.

It’s hard to know where to start to talk about the game, mostly because we need to establish some concepts, first.

Roguelikes (and roguelites) have many defining qualities, as defined by their enthusiasts. If someone asked me to define them, my shortlist of rules would include:

- The gameplay is focused on cycles. If you die, you’re brought back to the start, and you begin a new “run” from scratch.

- The gameplay takes place in a randomized (or semi-randomized) set of levels or rooms. While sections may be pre-generated or re-used, their order is not fixed.

- Along a typical “run”, you make choices that can improve your character’s journey. The way you stack and find synergy between these choices influences how your run plays out.

Hades falls into the “roguelite” category because it allows for permanent growth in between runs, which allow for the player to overcome challenges later on that they couldn’t on their first-ever attempt. This metagame (the “game outside the gameplay”) means that your motivation falls into a state of flux: are you doing runs because you want to progress things outside of them, or are you doing things in the metagame to make your runs more satisfying?

The first roguelite that really clicked for me was Cellar Door Games’ Rogue Legacy, which encouraged you to collect money and blueprints in your runs to spend in between them. You couldn’t amass gold, since it would be taken from you at the start of each run, but it spending it still gave you passive bonuses to health, damage, and other stats. Your 50th run would be vastly different than your first in terms of how it played.

In a card game, like Mega Crit Games’ Slay the Spire, failed runs count as progress, with milestones unlocking new cards and relics that influenced the game. Again, your 50th run would likely have much more choice and possibility than your first, even if there wasn’t a direct “your game is now easier because you’ve played it a lot” system.

These kind of metagames are contentious among roguelike fans because it affects the game’s focus. Without one, the game’s whole purpose is doing runs, and improving how fast or efficient your runs are is why you play. This genre’s notorious difficulty is also borne from this thought, because if you could beat it on your first attempt, you wouldn’t be going through the trial-and-error and growth that many would argue is necessary.

To purists, a metagame gives people who can’t (or won’t) improve a way to still experience the whole game, which defeats the point. Having the same system from start to finish, with success based on mastery of this system, is what leads to the most satisfaction for the player.

What’s interested me so much with Hades is that it plays off of that “point” and has worked it into the DNA of the game.

Combat, refined

Before we get into that metagame, I wanted to talk about how Hades plays.

Hades is very similar to Bastion and Transistor in their controls; you’re viewing the game from a three-quarters isometric camera angle, and that you’re typically using a mouse or controller to orient your character to where you want to engage.

If you have a bow, or a ranged weapon, your movement means getting line of sight and staying out of reach while you charge a shot. For melee, you’re typically using invincibility options (rolls, dashes, etc) to avoid damage while getting into a position where your weapon does the most damage.

Pyre, despite being more of a sports game, still requires a lot of focus when it comes to movement; how your team racks up score while staying alive in the process takes forethought, tactics, and understanding of the system. While it avoided “kill the bad guys” for its purpose, it still thrived in a ritual similar to combat, like American football or rugby.

Coming back to Hades, I noticed that it plays significantly faster than Bastion, and it took cues from Transistor in terms of adding more options for movement and preventing damage.

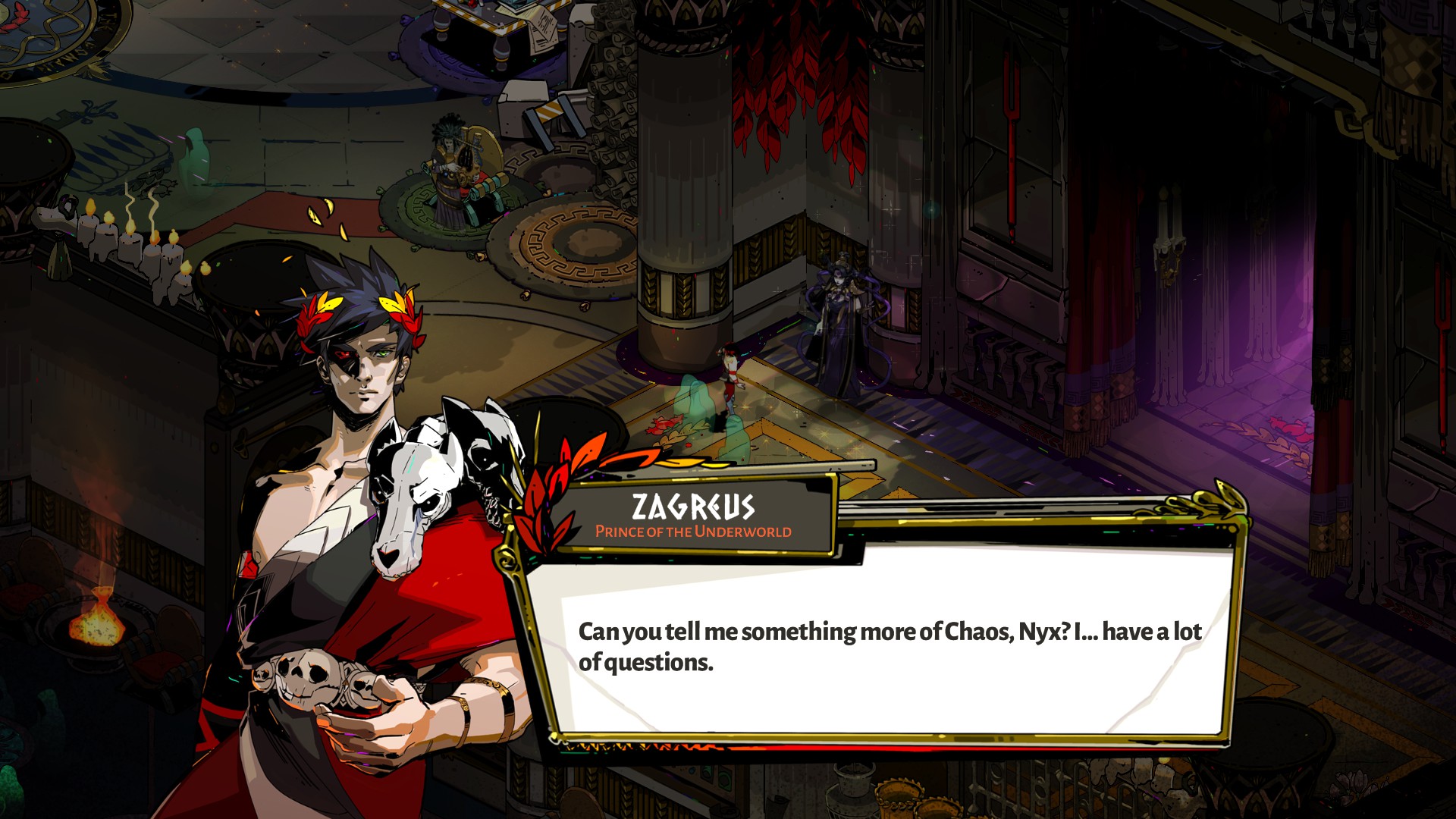

Zagreus (the protagonist) has a moveset depending on which weapon he’s using, similar to Bastion‘s arsenal; it’s up to the player to figure out what suits them best, and over time, they’re encouraged to use every aspect of their kit. He can also dash, which is a core element of the game — if you’re not moving, you’re probably dying.

On the surface level, it’s really to see this as shallow, but the nature of the roguelike means that we’re getting multiple ways to grow and augment our power set over the course of a run.

Rolling, rolling, rolling

Hades has you traversing a number of rooms, 12 at a time, spread across three separate worlds. In each room, you’re given a reward for completing it (killing all enemies, usually). In some rooms, the paths branch, and you choose which door has the reward you’d like most; each upgrade or collectible has an icon above the door leading to the room, which signifies what you’re getting.

Most permanent upgrades take the form of Boons; they first show up as icons, each unique to an Olympian god who wants to see you succeed. Interacting with the Boon makes a roll on a table which determines which three you can choose from, and they can modify different parts of your kit.

Once these get rolling, it becomes an interesting set of choices that affect how your character plays, and how successful they are. Making a successful build often requires a lot of experimentation and knowledge that comes from bad choices and failure — when you’ve cracked the code of which ones work well together, suddenly Hades becomes about praying to the loot gods that your rolls fall in the best places, and improvising if they don’t.

And what if they don’t?

You die, you get back up, and you start again.

Story in cycles

An issue with roguelikes/lites is that it can be very difficult to tell a story. Because you’re encouraged to repeat the gameplay loop, it’s just a matter of where it can fit in. Some games will throw you scraps of journal entries that you can find while adventuring, or codexes that fill themselves out as you experience new things.

Hades is unique, because how it crafts its narrative is both thematically appropriate, and works tremendously well from a game design perspective.

When you die in Hades, you walk out of a blood pool, back in the game’s hub, the House of Hades. Here, you’ll find a lot of the other characters you’ve talked to on your journey (not the Olympian Gods, but moreso the Cthonic ones, or some of the side characters that are kind of just doing their job). Being able to interact with these characters gives the game some much-needed breathing room, and also allows you to advance relationships with them through dialog and gifts.

This “social link” system is very much appreciated, because it makes you consider where you’re going to spend your Nectar or Ambrosia (gifts to advance individual plots) that you pick up in the world. The Olympic gods also take gifts and have their own plots, but you can only advance them when you’re about to pick up your boons.

It all feeds into this narrative of cyclic futility that makes a lot of sense when you consider the players at work: these are gods who are used to their place in the world, and the universe essentially railroading them into a sense of duty and purpose. In the House of Hades, it’s very clear that despite the game’s narrative goal being escape, you can never escape.

This is pretty interesting when it comes to character interactions because death and rebirth are seen as not that big a deal. You can even have an ongoing conversation with Megaera, the game’s first boss, who has some issues with Zagreus but also references previous defeats, victories or what progress he’s made on his quest.

This almost feels like another day at the office to them, like if Mario was meeting Bowser at the bar between game overs. It helps to lessen something that turns people off of Roguelites, which is the feeling of futility by being “walled” by a challenge they can’t surmount.

With the incentive of advancing the plot between runs, and through getting more access to characters they like, losing becomes less of a disappointing event and more an opportunity to work on the “game outside of the game.” Nothing feels like a waste, which is something that I struggle with with other games of the genre.

I recently read Derek Yu’s book on Spelunky, a titan of the roguelike/lite genre, and a chief example of the gametype having both its detractors and proponents. To Yu, Spelunky should be hard and frustrating, because the joy comes from beating a challenge that the player achieved through knowledge, rather than in-game growth.

Many people (myself included) can bounce off Spelunky for seeming unfair or difficult, but it comes down to a pseudo-carrot-on-a-stick. We need that motivation that sates our desire for progress, or at least something to soothe our egos when a good run is lost to something we perceive as unfair, or our own actions.

Tumblr, the genre

Some people respond better to these punishing learn-by-losing games, and others don’t. I get the idea that SuperGiant knows what kind of audience they’re going after.

Besides the meta-narrative and the idea of permanent progression currency (spent to beef up Zagreus’ starting state, which smashes a roguelike purity), the overall design caters to a brand of gamer who desires distinct, fleshed-out characters which interact with both the player character and each other.

If those characters can gain/lose relationships, develop interpersonal drama, or otherwise be “shipped“, the community will set that property ablaze with cosplay, fanfiction, speculation, endless free marketing and a deep, emotional, personal attachment to it.

I don’t mean to sound callous when I refer to it as a “Tumblr audience”, but that’s a generalization that’s borne from me seeing multiple of these types obsess about Doctor Who, Supernatural, Twilight, Harry Potter, Sherlock, Hannibal, the Yakuza titles and many, many others.

This isn’t meant to be a bad labeling, just one I think that the game development community is acutely aware of: I am 99% certain that SuperGiant designed the characters in this game, as well as the narratives they take part in, to partially pander to that audience.

And you know what? That’s okay, because it doesn’t impact the game whatsoever. All of the characters are likeable, and all of the interactions they have seem well-thought-out, developed, and purposeful. No one is just there because they would sell more games, and I can appreciate the artistry and planning that it takes to deal with that.

Downtime in Hades

Bringing this back to the downtime aspect, I think it’s important to highlight just how hard it is to combine all these features into something that plays well:

- The gameplay itself is quite difficult.

- The narrative is engrossing.

- The characters are likeable.

- The challenges are varied enough to be able to provide random runs.

- The progression of unlockables, either cosmetic or functional, has a great curve.

- Experimentation is encouraged.

- I never feel like I am wasting my time, or that a run was not worth doing, even if I lose.

I think that last point is probably the hurdle that most games that strive for longevity struggle with. Because of the amount of access to cheap-or-free games that the average gamer has, there’s a possibility that our attention is very limited, and the desire to surmount a challenge can be overshadowed by something we’d rather do more.

If Hades didn’t hit all those points in terms of aesthetics, progression, variety, and fun, it wouldn’t matter how fun the gameplay was, and vice versa. Everything needed to come together, and thankfully SuperGiant’s other games played a large role in building experience.

Bastion

With Bastion, SuperGiant learned the basics of three-quarter view isometric combat, albeit as a slower pace than Hades’. They learned how effective narration was, and played with that in Hades with having Zagreus respond to the narrator, breaking the fourth wall a bit.

They also learned the benefits of limiting a moveset; the Kid has two weapons with two attacks each. These are further customized with five sets of two binary choices — choose one upgrade or the other for five tiers.

In Hades, Zagreus has one weapon (with two attacks), a Dash and a Cast spell. Each of these can be augmented with boons for new combinations and effects, but only once per “slot”. For instance, if my main attack chains lightning from Zeus, it will be overwritten by Artemis’ chance-to-crit property if I choose her boon.

Hades also takes lessons from Bastion‘s shield mechanic, where just-in-time guarding could send projectiles back at their caster. However, Hades makes Deflecting a theme of Athena’s boons, meaning that people have to make the choice to be more defensive.

Transistor

Transistor‘s slot-based inventory system likely morphed into Hades‘ Boons, considering their synergy; while Red could swap in and out what she wanted, Zagreus has to sacrifice what he already has, or “sell” a boon for a small amount of money. Less choice, more risk.

Transistor also had a similar Dash mechanic to Zagreus’, which ups the speed and introduces more “speed = survival” mechanics. Again, Transistor gave you four slots to choose skills with, and then use the leftover skills from the pool to augment your choices; this all feels like something that Hades learned well from in terms of the Boons, their synergies, and making choices based on functionality.

Overall, Transistor‘s combat is faster and more strategic than Bastion‘s was, but had the ability to freeze time and plan out actions at the cost of a refillable gauge resource. Hades has no such system, but the pace at which enemies spawn was likely influenced by the lessons SuperGiant learned about combat pacing.

Make the game too hardcore or too overwhelming when it comes to combat, and they lose that potential casual audience that won’t be able to rise to the occasion.

Pyre

While Pyre probably has the least in common gameplay-wise with Hades, it has the most when it comes to narrative structure.

In Pyre‘s world, completing a sequence of trials means the player can choose one member of their pseudo-sports team to be set free, out of the game’s purgatory. After being freed, the character is absolved of their sins, and takes part in an unseen revolution.

After doing so, the player gets a bit of the overarching story, but a cycle is also reset. They needs to find a new character to take the freed one’s slot in the team, and are able to take the journey again to free more of their friends. Again, freeing more friends gets more plot, and story beats along the way — you learn of what your freed friends are doing, and have interactions with the rival teams who are also trying to earn their freedom.

What I didn’t like about Pyre was its over-reliance on text; I felt like I was reading through a visual novel with minor sports breaks, rather than playing a game where both the gameplay and story complimented each other.

There was also the sense of you spending less time among your team and more time in menus. While you initiated conversations from your caravan by clicking items, it felt difficult to engage with characters when they did little else but pop up when prompted. They weren’t actually living in the world beyond your interactions with them, and the nature of the plot made it difficult to grow attached to them, only to ultimately choose to let them go free Yes, I know, this is the point. I just didn’t like it very much.

Hades does a great job of learning from the pacing and changing what the player learns, and when; you’re only unlocking one new conversation with someone per run, but it never feels like it’s too little. With so many people to talk to, you never feel like you’re just grinding until you get to what you really want.

I suppose that’s ultimately why it’s catching on with so many players, and why the wealth of content never seems overwhelming or too much of a challenge.

It hits this weird area of being an evolution of a genre while also not. The roguelike is purposefully obtuse in some ways, and there’s this sense of conflict towards what the grander public may want vs what its core enjoys. While there’s always arguments for and against gatekeeping and elitism, Hades feels like it’s going its own way, and I fear that its success may push the roguelike/lite as a genre away from what it was defined by initially.

Instead of focusing on that feeling of conquering the odds with only your knowledge of the system, Hades perpetuates the idea that more users want more ways to gradually improve and having every run mean something in terms of tangible, in-game progress.

While purists might scoff at that idea, I think Hades probably achieves it the best simply because SuperGiant aren’t throwing a handicap system onto another game and calling it a day. What I like about their games are that sense of progression and learning as a company, and a deep understanding of the systems that make up something that people genuinely are attached to.

Throughout the game’s development, there was a general sense of “yeah, this is really polished, and now they’re adding a boatload of content.” That’s the kind of relationship that you want to have with your fans, because it builds trust that they know what they’re doing when it comes to design, and how to execute something great.

So bravo, Hades — keep it up. The day I finished writing this I got my first “win”, and unlocked a whole other tier of challenges, handicaps and ways to get more progress. It still hit that feeling of “hell yes” when I finally got that final hit, but the mountain of new things didn’t feel like it invalidated it.

I might let it cool off for now and let that victory ride, but I’m almost certainly going to go back for more.

Note!

Starting in 2023, more of my writing will be on Substack, with only certain, personal posts making their was to this site. Consider subscribing to support my work.

Amazon links on this post may be affiliate links to help support Matt.

Leave a Reply