I’ve fallen down a hole in watching a particular streamer, and most of why is what he’s running. Iateyourpie is a variety streamer that seems to have figured out why certain formats of Twitch streams are entertaining, and the more I hear him talk about it, the more his choices make sense.

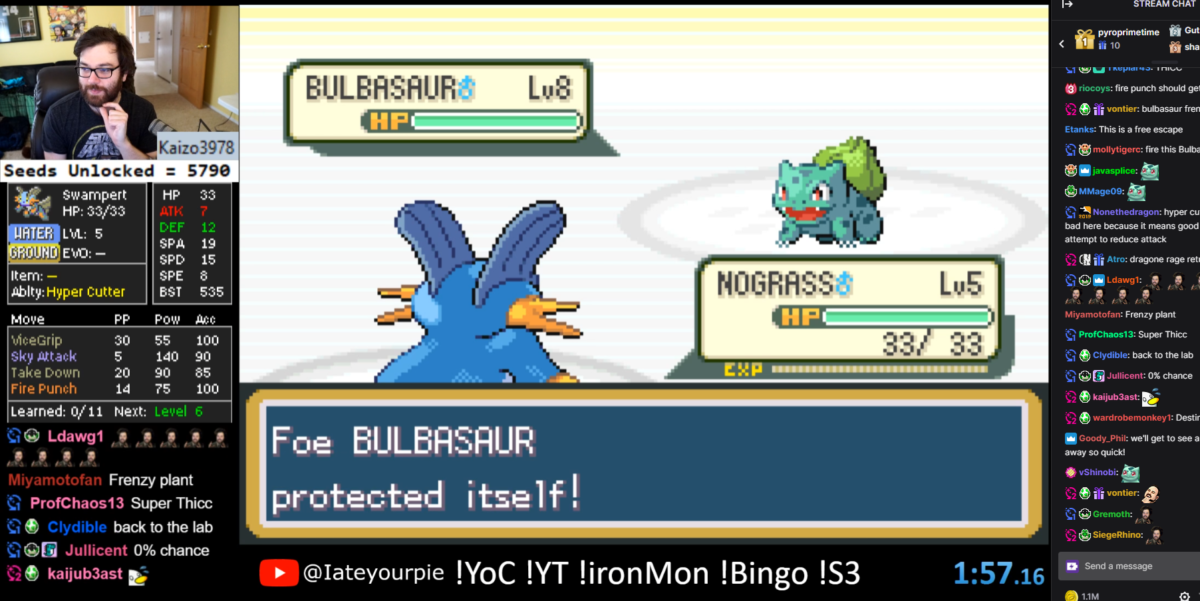

His creation, “IronMon”, follows the popular practice of creating challenging rulesets for the Pokemon franchise of video games. Bluntly, the Pokemon games are pretty easy, and adding limitations or randomization has given them new life in terms of asking people to watch them live.

The rules of IronMon aren’t exactly important; you’ve got three flavors of the challenge, each with escalating levels of difficulty. However, what is important is how they hit different aspects of what makes a successful Twitch stream.

Qualities of an entertaining Twitch stream

Below I wanted to create headers of what I think the “secret sauce” to a successful stream is, and how IronMon is crafted to hit those moments hard in a sustainable way. That sustainability is important, because the person running the stream has to be able to avoid burnout along the way.

In a simple list, I think a successful large-scale Twitch stream has the following qualities:

- Hype moments from a visual perspective. Clip-worthy moments that share easy to show the appeal of the stream

- A shared context, where people can be onboarded to the stream’s value quickly, and get continued value with more investment

- A degree of randomness to ensure a variety of hype moments, without breaking the shared context too hard

- A leveraging of Twitch’s Points wagering system to encourage long-term attachment and retention

- Meme generation capabilities, both in the sense of hype moments informing new ones, and references/lore that can be both celebrated and monetized through merch, or other incentives

- A sense of valuing the time of both the viewer and the streamer. Especially in challenging rulesets or speedruns, there has to be a pacing that ensures someone who spends time in the stream comes away from the time spent positively. Also, the streamer has to be able to enjoy the time spent

I think it’s easy to look at the list above and think that it’s taking a lot of fun and spontanaety out of streaming, but I believe that more streamers who want to perform at a high level need to do this kind of project workshopping. While we’ve heard and would like to believe that “it doesn’t matter what you stream, as long as it’s you doing it, some games perform better than others for specific reasons.

I’d like to expand on those reasons, and how they come together, below.

Hype Moments

Because of the infrequency of a run making it past a certain point (be in “making it out of the lab”, or past the first Gym Leader, Brock), moments can be made hype just by existing. Since Brock represents a particularly challenging wall of difficulty, Pie enhances the experience by playing “Pledge of Demon” from Yakuza 0; you truly feel like it’s a special boss, even above the storyline bigger ones in the game.

Of course, the ability to sell a moment as momentous comes down to a streamer, and someone who doesn’t celebrate a moment as being amazing or terrible isn’t going to have that enthusiasm bleed over to their audience.

I firmly believe Twitch streaming has a lot of commonalities with pro wrestling in that the psychology of the moment is determined by how believable the performer is. Being genuinely excited or dismayed is difficult to fake, and having people react as you would means it becomes collaborative.

Part of esports is the challenge of taking moments that are complicated and making their meaning immediately understandable to a layman audience; a lot of the strength of IronMon comes down to the format, but Pie’s enthusiasm and ability to sell things as important is something that he does very well.

Shared Context

RPGs are about the adventure, and conveying that feeling of “the long journey” to an audience can be difficult. I’ve written about streaming story-based games in the past, and you end up running into a couple problems.

- If an audience member isn’t there for the whole thing, they lose context in the long-term adventure.

- If the audience member is planning to play the game themselves, they don’t want to be spoiled.

IronMon and other challenge rulesets work because Pokemon isn’t exactly known for its strong story, and it’s a familiar enough format that people don’t need to do a ton of learning in order to understand what’s going on. If they’re heard of or played one of the biggest gaming franchises in history, they can enjoy a stream: they know the goal is to get a strong Pokemon, and see if you can become the Champion of the region.

Runs like IronMon work because there isn’t a huge onboarding period, and anyone can jump into a stream to know exactly what to expect. Especially if they’ve played the game that’s being run, they know how they played it, and that provides context for the difficulty (or “uniqueness factor”) of the challenge.

This shared context is the basis of all sports/competition fandom: because people know how well they can play, they can appreciate when it’s done by someone else, better. Pie has specifically mentioned it as being why he plays Pokemon FireRed; it features locations and Pokemon that people are likely to be most familiar with, since it’s a remake of the original Pokemon Red version.

Randomness and Gambling

Since every run of IronMon is randomized, there’s always the carrot-on-a-stick motivator of “this run could be the one.” Even if the previous one was completely hopeless, it’s very easy to regain hope, or at least generate the hope from the audience.

This randomness plays into Twitch’s point gambling system, which is basically a metagame of Iateyourpie’s IronMon streams. Being able to bet channel points on outcomes means that the viewer gains investment into the outcome, even if that outcome isn’t a large amount of progress in the challenge.

Being able to mitigate disappointment is part of this grind-heavy challenge, and if people don’t think that fun moments are possible, they won’t watch in the first place.

Well… we go again.

— Iateyourpie, 2022

At the end of the day, failure doesn’t matter, because success isn’t necessarily the point of the ruleset. IronMon balances chat interaction with new things happening at a pace that allows for memorable moments to be shared, reacted to, and built into a shared context.

Someone who gifts a Subscription gets to choose which Pokemon Pie chooses at the beginning of the run (left, right, or center). Someone following the channel for the first time gets 300 points for gambling with. This cumulative “points earning” allows people to craft their own narrative separately from what’s actually happening on stream: if you know your stuff, it doesn’t matter if Pie wins or loses, because you can win, too.

Meme Generation

Every time Pie loses a run, he’s sent back to “The Lab” where Pokemon stories start. In most cases, Prince Paul’s “Back to the Lab Again” will accompany him, as a sound clip plays if a user donates 250 Twitch Bits (equivalent to $2.50).

It serves multiple purposes: it can be a celebration, a rubbing of salt in a wound after a painful running, or just a general “we have had terrible luck today” corroboration. This memeability works in Pie’s favor, because if we assume that this alert has played at least once per reset (sometimes it’s played multiple times, others, none), he’s made almost $10,000 USD from the current “season” of IronMon (as of writing, he’s gone through 3934 seeds).

I feel a bit conflicted pointing that out, because I don’t want it to paint the act as malicious, or some kind of exploitation. If a product can generate its own culture through memes, lore and references, and participating in that culture can be monetized, it’s probably a very good thing for the financial viability of the stream.

Because we’re watching the same context being played out in different ways (same adventure, different characters), when things do repeat, you have the previous history to create a reaction. For instance, a Blastoise (nicknamed “Baja Blast”) derails a really good run, and from then on, that memory sticks with all appearances of further Blastoise. The Rock Tunnel becomes “Rick Tunnel.” All Eevee-lutions get nicknamed “Bob”. Simple.

The ability to make a viewer feel invested over a long period of time through the participation in culture means they’ll return for new streams, view for a long period of time, and engage in premium experiences (subscriptions, donations, etc). These are all very good things, and they’re a result of a community that’s into what it’s viewing.

Valuable Time Commitment

If we ever win with a ‘Mon like this, it will be a roller-coaster of an adventure. It will be an incredible— it will be like taking The Ring to [Mount Doom].

— Iateyourpie, 2022

IronMon runs can end up being minutes-long, or a tense occasion that stretches into hours, or multiple streams. Pie has repeatedly referred to IronMon as potentially “Just Chatting, only with things maybe happening”, and failure “still being good content.”

Being able to still maintain an entertaining product through a massive amount of in-game failure, or repeated slow periods of progress means that the streamer themself doesn’t see this as a waste of time.

Because the purpose of the run is partially to have high chat interaction while doing something inherently entertaining (largely divorced from individual skill, beyond knowing specific interactions of Pokemon), the chat still finds value in what’s being generated.

It’s easy to come away from this thinking that the format is what’s carrying the stream, but it’s moreso a balance of the value proposition of the stream mixing with the experience of the streamer. Pie knows just when to shill features (“If you follow now, you get an immediate 300 points to gamble with”), and this only comes with an understanding of the rhythm and cadence of a stream.

The purpose of this article was to point out that you can both purposefully craft something entertaining while keeping it authentic, and more streamers need to embrace that part of their job.

As the streaming ecosystem gets more saturated, these kind of innovative experiments — not just following someone else’s successful format — are what streamers are going to need to survive.

Note!

Starting in 2023, more of my writing will be on Substack, with only certain, personal posts making their was to this site. Consider subscribing to support my work.

Amazon links on this post may be affiliate links to help support Matt.

Leave a Reply