I think my favourite manga genre is “hard work makes good”, which is hard to describe. Usually it has a couple similar tropes/beats and qualities:

- The protagonist is flawed; not too stupid, but incompetent in the way that’s kept them from being particularly successful.

- The protagonist has a passion or talent that allows them to rise above the disatisfying place they’re in. This can be as simple as or stereotypical as “I can work harder than everyone else.”

- The protagonist eventually finds a place where they can thrive, and people that support them. If the protagonist has no relationships (romantic or otherwise) before the story begins, they will gain them during the course of the plot.

- The protagonist will have roadblocks in the form of themselves, their industry, or rivals.

- The protagonist will overcome these roadblocks, or have to compromise in a way that still enables them to grow as people in the process.

It’s clear why I like these kind of series: it gives me hope that I’ll be able to make the same kind of changes and achieve the same kind of success. However, something I’m self-aware of is that the control the creator has over their manga. They get to choose when their characters succeed or fail, and the pacing of the story builds around a plan.

This slows down the amount of inspiration I get from these series, especially in one glaring case: if the plot centers around the achievement of the goal instead of the development of the character.

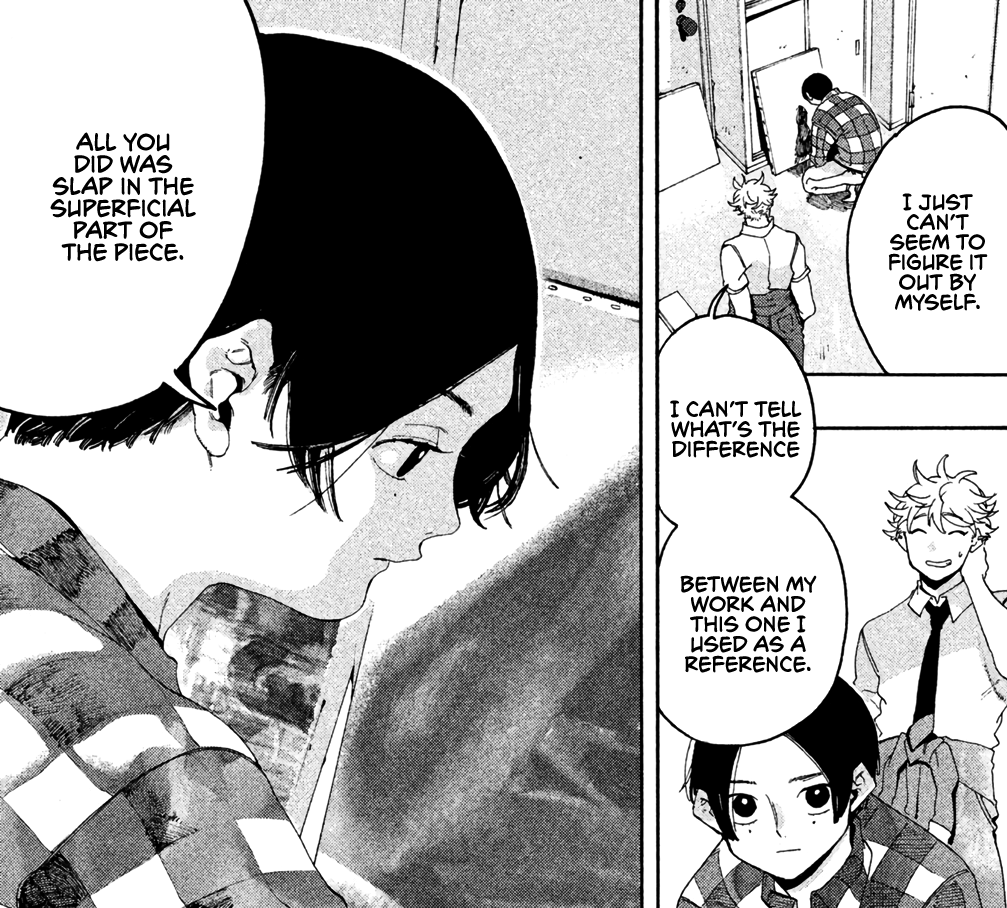

Change and difficulty can occur externally, or internally. An editor losing a mangaka’s manuscript, keeping them from applying to an award is an external problem. Overcoming a creative block after lengthy introspection is internal. I’d argue these internal conflicts are much, much more interesting.

Which leads us to Tsubasa Yamaguchi’s Blue Period.

At first glance, the series has a lot of what I described above as problems: the protagonist, Yatora Yaguchi, is a deliquent, yet gifted academically. This is the classic “flawed, but only superficially” characterization that hurts a lot of manga: if the characters have something wrong with them, it either isn’t going to impact them negatively, or is easily discarded as the story gets going.

Yatora’s deliquintism isn’t a big focus on the story. He’s not a partier, nor is he violent or working in crime. For the most part, he just goes out for (underage) drinks with his boys, and seems to be the one making sure they get home safe at the end of the night.

Usually this would be another metaphorical strike, mostly because again, there’s nothing inherently difficult here; saying “ah yes he’s also a study nerd” keeps the consequences of his actions from catching up with him.

Where Blue Period succeeds is making it so that Yatora’s journey isn’t so much about his desire to be successful, rich, or famous, but his desire for personal fufillment. He feels empty while proceeding towards the life he’s built up to this point, and yearns for a change. His goals take a turn, and he decides to try to both learn art and get accepted to a prestigious Tokyo art university; this is the destination of the story, but thankfully doesn’t matter too much.

Yatora’s development isn’t so much about hitting those milestones of “learning the basics, then applying for a small contest, then studying for an entrance exam, then…”, which would be the forumla of similar manga. Those events still happen, but they serve as a backdrop to his development as a person. Yatora desires his life to mean something, even if that meaning is coming from himself, not society.

It would be easy to look at Blue Period as some kind of repudiation of Japan’s harsh work culture, but it isn’t. There is no ignoring the impracticality of the art world (especially at a professional level), and Yatora’s journey takes him through multiple different viewpoints on creating, the venues of creation (like taught vs untaught artists) and how it all affects his perception of his craft.

Certain chapters are less plot points and more “the author researched this area of art, and found it really interesting.” Exposition informs the reader through Yatora learning more, too; it can feel like reading a Powerpoint at times, but it really shines when the characters are impacted emotionally, later.

Creating is a personal act, and I think that’s why I like exploring it through PlusHeart. There’s a feeling that happens internally that explodes outwards onto the medium the artist chooses, but there’s still this layer of pragmatism that has to come along with it. Blue Period doesn’t ignore the idea that artists need to struggle to “make it”, and even if they do, where they land might not be the most sustainable, either.

My favourite parts of the manga (so far) are the story beats that mirror parts of my life — namely, the ones where Yatora is depressed, art-blocked, and considering the motivations of his career. Being able to toy with questions of selfishness or ignorance (or just the feeling that you’re completely out of your depth) is something that I wrestle with often. Going through that crisis of “I just learned something new and it’s completely destroyed my confidence and perception of what is correct” confuses you, because you’re still learning how to be confident in your craft.

But, still, we pick up the pen, the keyboard, the typewriter, the instrument, or the painter’s tools. It doesn’t leave the realm of possibility that we’re suddenly going to stop; it feels too important or too loud within us to. Confidence only grows through attempts, mistakes, and reflection.

Maybe that’s me projecting my own main character syndrome a bit, but if these kinds of stories don’t put you in that mindset, I don’t think they’re doing their job properly.

I’ve only spoken a little about Yatora’s journey, but I think that the secondary protagnonist, Ryuji Ayukawa, also offers good story beats around identity, creativity, sexuality, and positive LGBT representation. I don’t feel qualified to give it a thorough examination, but I think it’s handled better than most manga. Her story is a bit more personal (and personal conflict-heavy) than Yatora’s, but it fills in something much-needed.

Blue Period isn’t a particularly difficult read, but it hits those “art school vibes” that I think anyone creative has had to deal with, even peripherally. This piece came as a result of me wanting to write about Chūya Koyama’s Uchū Kyōdai (“Space Brothers“), and finding that a lot of the criticisms I have about “hard work makes good” stories are present. I think it’s valuable to contrast multiple titles, mostly because you can find explanation in who the audience is, or what themes the series is trying to address.

With Space Brothers, a linear storyline kind of falls off, because the main characters’ flaws are resolved and minimized fairly quickly. He cannot stay that person while striving towards a lofty goal, so the series becomes about achieving those specific milestones, without a lot of tension towards whether he can.

With Blue Period, the journey isn’t about the art, or the goal of the university, the art exhibit, or the career. It’s about looking at how art (and trying to be creative) can be intensely challenging, and how that changes you in the process.

I think that regardless of whether you’re artistic or not, you can find something to identify with, there.

Note!

Starting in 2023, more of my writing will be on Substack, with only certain, personal posts making their was to this site. Consider subscribing to support my work.

Amazon links on this post may be affiliate links to help support Matt.

Leave a Reply